The U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling on Friday that states that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (a statute from the 1970s) does not grant President Donald Trump authority to issue global tariffs. The court struck down Trump’s claim with a 6-3 ruling.

Trump has already invoked the act to implement tariffs on imports from other countries throughout 2025, including:

- “Fentanyl” tariffs aimed at China, Canada and Mexico to encourage those countries to increase efforts to stop the flow of fentanyl and its precursor chemicals.

- Global “reciprocal” tariffs on imports from almost all countries to address trade deficits that Trump declared a national emergency.

The ruling, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, claimed, “The president must ‘point to clear congressional authorization’ to justify his extraordinary assertion of the power to impose tariffs. … He cannot.”

Chief Justice John Roberts

Supreme Court Ruling

- It’s important to note that this ruling does not affect the specific tariffs on steel and aluminum, which were not issued under the IEEPA and affect merch categories from drinkware to signage.

This is potentially a landscape-altering decision. While it could bring huge relief to businesses affected by tariffs, it could also cause an unprecedented degree of confusion and uncertainty in its aftermath.

“This ruling is a mixed bag,” says Rachel Zoch, CAS, PPAI’s public affairs manager. “While we know that tariffs and changing rates over the past year have creating pricing challenges and cut into profit margins, especially for suppliers, the Supreme Court’s decision triggers a whole new round of uncertainty.”

Are Tariff Refunds Coming?

It is hard to parse out the legal answer to that question and the sheer magnitude of making something like that happen.

- While there seems to be a clear legal argument for tariff refunds in light of this decision, the majority opinion does not explicitly discuss refunds or provide a framework for how that process should be enacted.

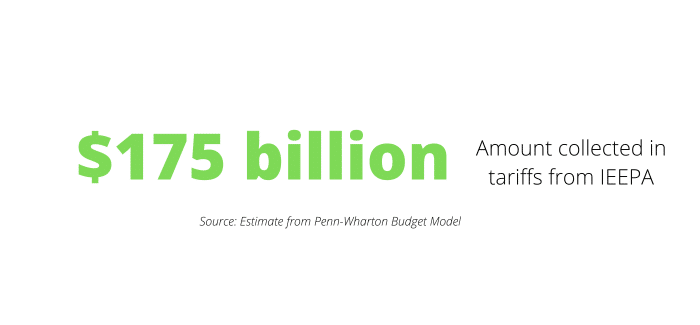

- According to Penn-Wharton Budget Model economists, more than $175 billion has been collected from tariffs citing the IEEPA and would need to be refunded.

This particular part of the equation will be the most noteworthy to watch going forward, with many invested parties. For now, it is unclear whether a path to refunds will be established and what that would look like. In the event that one does present itself, it is likely to be a drawn-out process.

Trump Will Not Give Up On Tariffs

While this ruling represents a significant loss for the Trump administration’s agenda, it is not one that the president and his staff were unprepared for. Tariffs are unlikely to completely go away. Trump will attempt to reinstate as many as possible through means other than the IEEPA. As discussed in a column in The Hill shortly before the ruling, this will not be easy, as the IEEPA granted the president much more freedom to enact tariffs at his discretion.

As Politico reported, White House aides “have spent weeks strategizing how to reconstitute the president’s global tariff regime if the court rules that he exceeded his authority.”

Trump has at least five fallback options to impose tariffs in different ways, according to Bloomberg:

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962

Section 232, which Trump used during his first term in office, gives the president power to use tariffs to regulate the import of goods on national security grounds. Unlike the blanket tariffs Trump imposed using IEEPA, Section 232 is designed to be applied to imports in individual sectors, rather than from entire countries.

However, the president can only act after an investigation by the Commerce Department determines that importing these products threatens to impair national security. After a probe is initiated, the Commerce Secretary must report the conclusions to the president within 270 days.

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 201, which Trump also used during his first term, authorizes the president to impose tariffs if an increase in imports is causing or threatening serious injury to American manufacturers.

- The tariffs are capped at 50% above the rate of any existing duties.

- They can be imposed for an initial period of four years and extended to a maximum of eight years.

- If the levies are in place for more than a year, they must be phased down at regular intervals.

Before implementation, the U.S. International Trade Commission must conduct an investigation and has 180 days after a petition is filed to deliver its report to the president. Unlike the Section 232 probes, the ITC is required to hold public hearings and solicit public comments.

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 301, which Trump also used during his first term and was used in July, allows the U.S. Trade Representative to impose tariffs in response to other nations’ trade measures “it deems discriminatory to American businesses or in violation of U.S. rights under international trade agreements.”

- The tariffs automatically expire after four years unless USTR receives a request for continuation.

Before implementation, the USTR must first conduct an investigation, which includes requesting consultation with the foreign government whose trade practices are being probed and soliciting public comments.

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 122, which has never been used before, gives the president the ability to impose tariffs to address “fundamental international payments problems,” such as “large and serious” U.S. balance-of-payments deficits, an international balance-of-payments disequilibrium or to prevent an “imminent and significant” depreciation of the dollar.

- The tariffs are capped at 15% and can only be imposed for up to 150 days.

- Congressional approval is required to keep the duties in place for longer.

Section 338 of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930

Section 338, which has never been used before, empowers the president to introduce tariffs on imports from nations “whenever he shall find as a fact” that these countries impose unreasonable charges or limitations or engage in discriminatory behavior against U.S. commerce.

- Tariffs are capped at 50%.